CENTERVILLE – “Are their paws in danger?” asked long-time Centerville resident Gale Klun as she walked her three English Cockers along the banks of the Centerville River, which was recently dotted with creatures that appeared to be jellyfish.

CENTERVILLE – “Are their paws in danger?” asked long-time Centerville resident Gale Klun as she walked her three English Cockers along the banks of the Centerville River, which was recently dotted with creatures that appeared to be jellyfish.

Klun and others who frequent this popular dog-walking area have seen these sea animals—clear in color, with reddish lines inside their bodies—washed up during previous fall seasons, and have steered their dogs away for fear of a sting.

Town of Barnstable Natural Resource Officer Chris Nappi identified the animals as non-stinging comb jellies, which are commonly pushed ashore by wind or currents.

Nappi explained that the reddish lines “are actually ‘cilia’ which the jellies use to move around and collect food, too.” The celia are also known as “combs.”

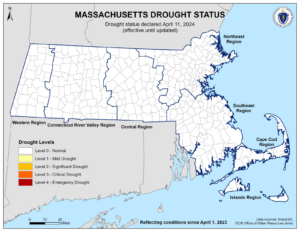

Recent research from 2006 and 2014 by two scientists at the NortheastFisheriesScienceCenter in Woods Hole suggests that comb jelly populations may have increased substantially in recent years. The authors attribute this increase to “a combination of local warming of water masses and overfishing.”

Although the creatures look like jellyfish, comb jellies are actually a different animal.

Both paws and feet are safe from comb jellies, but there are several types of jellyfish common to the area that are not as benign.

Amy Mahler, Assistant Press Secretary for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, cited the moon jelly and the lion’s mane as the most prevalent stinging jellyfish in our waters in the spring and summer months.

WHOI Sea Grant staff member Kate Madin confirmed Mahler’s observation, adding that the sea nettle, the purple striped jellyfish, and the notoriously dangerous Portuguese man-o-war (a jellyfish relative) are also sometimes seen.

“All of the species of jellyfish above except the moon jelly carry a strong sting, and can leave red marks and welts,” said Madin. “The most dangerous is the man-o-war, which has very thin, near-invisible tentacles, which means a swimmer can be hit with many tentacles at once.”

It is also important to remember that even when washed up and dead, jellyfish tentacles can still deliver a punch, so both people and animals should avoid them.

Madin further noted that a very small, invasive species of jellyfish from the Pacific called Gonionemus is currently raising concern on the Cape.

“(Gonionemus) is now living in some local coastal ponds…and has a very painful sting,” she said.

According to Cape Cod Hospital Emergency Center Medical Director Dr. Craig Cornwall, the most frequent type of sting seen in the Cape’s largest hospital comes from the lion’s mane.

“These occur in the late summer as the southern waters warm up, especially on days where the wind is out of the south and pushes them up against the shore,” said Cornwall. “Treatment is related to removing (tentacles) still on the skin without activating them. Vinegar helps inactivate them and shaving them off—with an actual razor and shaving cream or gel—is the least traumatic way.”

Cornwall recommends OTC pain medications, anti-inflammatories, and antihistamines for supportive treatment, or oral steroids for bad cases. Besides vinegar, the Mayo Clinic’s website and the Divers Alert Network suggest washing the affected area with salt—not fresh—water. If the sting seems severe or an allergic reaction occurs, seek medical attention.