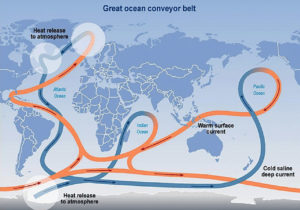

The constantly moving system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm, salty Gulf Stream water to the North Atlantic where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler, denser water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up to the Gulf Stream. (Copyright Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2001)

WOODS HOLE – New research provides evidence that the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean is at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years and hasn’t run at peak strength since the mid-1800s.

Researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who participated in the study with University College London believe the slow down began with melting freshwater entering into the Atlantic at the end of the last little ice age and has continued to weaken due to global warming.

“This has potential consequences for climate, weather, sea level on the East Coast, and fisheries,” said Dr. Delia Oppo, a senior WHOI Scientist and co-author of the study published this week in “Nature.” “It could really affect our daily lives.”

The circulation of the Atlantic plays a pivotal role in regulating global climate. The constantly moving system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm, salty Gulf Stream water to the North Atlantic where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up to the Gulf Stream.

Lead author Dr. David Thornalley, a senior lecturer at University College London and WHOI adjunct, believes that as the North Atlantic began to warm near the end of the Little Ice Age, freshwater disrupted the system which is called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Arctic ice sheets and glaciers began to melt which formed a huge natural tap of fresh water that raced into the North Atlantic Ocean.

This influx of freshwater diluted the surface seawater, making it lighter and less able to sink deep, slowing down the system.

Scientists examined the size of sediment grains deposited by the deep-sea currents, with the larger the size of the grains meaning stronger currents. They also used a variety of methods to examine near-surface ocean temperatures in regions where temperatures are influenced by AMOC strength.

“Combined, these approaches suggest that the AMOC has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15 to 20 percent,” said Dr. David Thornalley, a senior lecturer at University College London and WHOI adjunct.

Ocean circulation also distributes the mass of sea water. Sea level on the East Coast is relatively low and further offshore across the Gulf Stream the sea surface height increases.

“If the ocean circulation slows down and the Gulf Stream slows down then that slope relaxes and sea level on the East Coast rises,” Oppo said.

Oppo said a short slowdown of circulation in 2009 and 2010 impacted sea levels along the East Coast.

“If this continues it would further impact sea levels which is a huge thing on the East Coast,” she said. “Not only with ocean circulation declining, but we have warming that is expanding sea levels everywhere and we have melting from glaciers which is also increasing sea levels.”

Oppo said the circulation slowdown is exacerbating other problems related to global warming.

“It’s also possible that these severe East Coast winters are related to the slowing down of the circulation,” she said.

Another study in the same issue of “Nature,” led by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, looked at climate model data and past sea-surface temperatures to reveal that AMOC has been weakening more rapidly since 1950 in response to recent global warming. Together, the two new studies provide complementary evidence that the present-day AMOC is exceptionally weak, offering both a longer-term perspective as well as detailed insight into recent decadal changes.

Additional studies will be continued to extend the circulation records further back in time to other cold periods in the last 5,000 to 6,000 years.

“We want to study those and see if the ocean circulation recovers after the melting that follows those cold events or if the ocean circulation stays in a reduced mode for some period of time,” she said. “We want to really understand how unprecedented this long-term decline is and whether it’s really related to global warming as we suspect.”